At the heart of her work are the themes of female strength and mutual support, the struggle for racial dignity and equality, family ties, spirituality, and the preservation of cultural memory. Besides her writing, Gloria Naylor was an essayist, educator, screenwriter, film producer, and playwright. She actively engaged in research and preserved accounts of Black American life in the 20th century, leaving behind a valuable spiritual and cultural legacy. Read on newyorka.info for more about this advocate for freedom and equality.

Gloria Naylor’s Life Path

Gloria Naylor was born on January 25, 1950, in Manhattan to Roosevelt Naylor and Alberta McAlpin. Her parents had recently arrived in New York from Robinsonville, Mississippi, escaping the oppressive segregation of the South and seeking a better life in the North. Her father found work in the transit service, and her mother became a telephone operator. Despite having limited formal education, Alberta had a passion for books and, from childhood, instilled in her daughter a love for reading and writing.

Little Gloria spent hours jotting down her thoughts, writing poems and stories, filling entire notebooks. In 1963, the family moved to Queens, where her mother joined the Jehovah’s Witnesses community. Naylor showed remarkable abilities in school; she was placed in advanced classes and enthusiastically read 19th-century classics. However, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 was a profound shock to the young woman. Disillusioned, she postponed her education and embarked on a seven-year missionary journey to North Carolina and then Florida.

Returning to New York in 1975, Naylor enrolled in Medgar Evers College, initially studying nursing, but quickly realized that her calling was literature. Transferring to Brooklyn College, she earned a bachelor’s degree in English in 1981. It was then that Toni Morrison’s book The Bluest Eye entered her life—a work that changed her worldview. Afterward, Naylor began discovering the works of Zora Neale Hurston, Alice Walker, and other Black female writers she hadn’t known before.

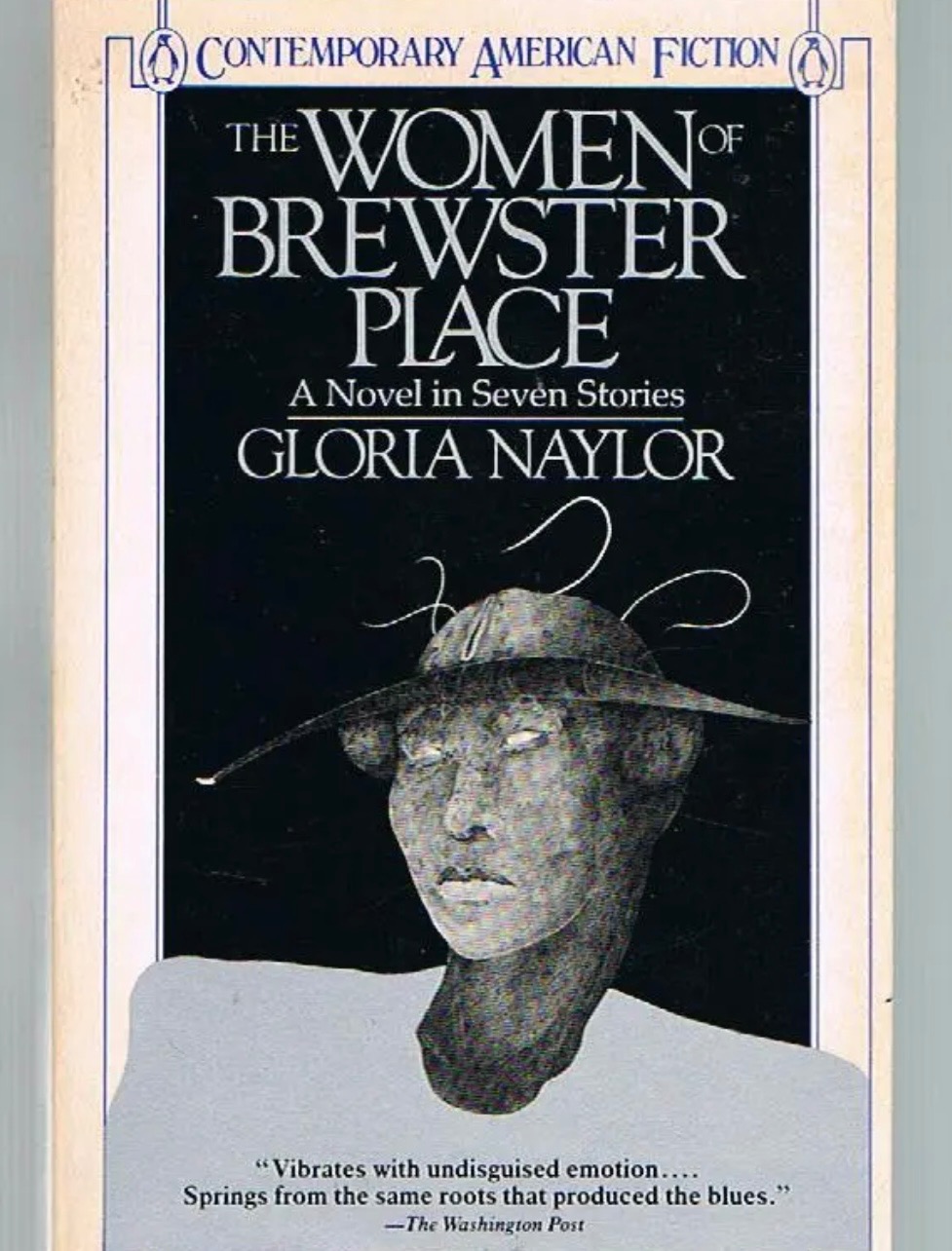

Her first publication was the essay “Life on Beekman Place,” printed in Essence magazine in 1979. This essay became the basis for her famous debut novel, The Women of Brewster Place. In 1983, Gloria earned a Master’s degree in African American Studies from Yale University—her thesis eventually grew into the novel Linden Hills.

This path, from a girl in a migrant family to an influential writer and intellectual, became an example of how the power of words is capable of changing not only the fate of one person but an entire generation.

Triumphant Debut

When Gloria Naylor released her debut novel, The Women of Brewster Place, in 1982, she immediately announced herself as a powerful new voice in American literature. This book is not just a story about seven women living in a rundown housing project; it is an epic about survival, pain, solidarity, and unbreakable dignity.

Through a series of interconnected stories, Naylor showed how the women of Brewster Place seek love and justice in a world often hostile to them. These stories contain everything—loneliness and friendship, rape and motherhood, homophobia and despair—but above all, the humanity that prevents these women from being broken.

Her prose is lyrical and harsh at the same time. In one of the most powerful moments of the novel, a neighbor tries to comfort a mother who has lost a child:

“As soon as she went to reach for the girl’s hand, she stopped, as if a muscle spasm had seized her body, and cowardly shrank back. Memories of old, dried pains were no comfort before this. They had the effect of cold drops of water on hot iron—they danced and evaporated, while the room stank of their steam.”

Critics were impressed. The New York Times noted Naylor’s courage in choosing the ghetto not as a backdrop but as the main stage of the action, rejecting clichés and stereotypes. Her heroines are not victims—they are alive, complex, and strong, each with her own voice and pain.

For this novel, the writer won the National Book Award for First Novel and the American Book Award. That same year, her work stood alongside The Color Purple by Alice Walker—another masterpiece that gave voice to Black women in America.

In 1989, The Women of Brewster Place came to life on screen again, thanks to Oprah Winfrey, who not only produced but also starred in the television miniseries. Alongside her appeared Robin Givens, Mary Alice, and the legendary Cicely Tyson. Despite controversy surrounding the portrayal of Black men, the adaptation became an event—powerful, emotional, and uncompromising.

The Women of Brewster Place laid the foundation for all of Naylor’s subsequent work. Here, she first spoke about what would become the core of her writing—poverty and racism, the burden of gender discrimination, and the fragility of hope. But most importantly, about the dignity and tenderness that women preserve even in the darkest moments.

Gloria Naylor’s Literary Evolution

Following her critical success, Naylor continued to write, never losing her social insight. Her second novel, Linden Hills (1985), modeled after Dante’s Inferno, exposed the spiritual emptiness and moral cost of materialism among affluent Black suburban families. In Mama Day (1988), the author masterfully combined folklore and Shakespearean motifs, creating a layered story about generational ties.

The novel Bailey’s Cafe (1992) transported readers to a mythical Brooklyn diner in the 1940s—a place where people worn out by life find solace and the possibility of healing. And in The Men of Brewster Place (1998), the writer returned to the world of her debut, this time showing the stories of the men who lived alongside the heroines of the first book.

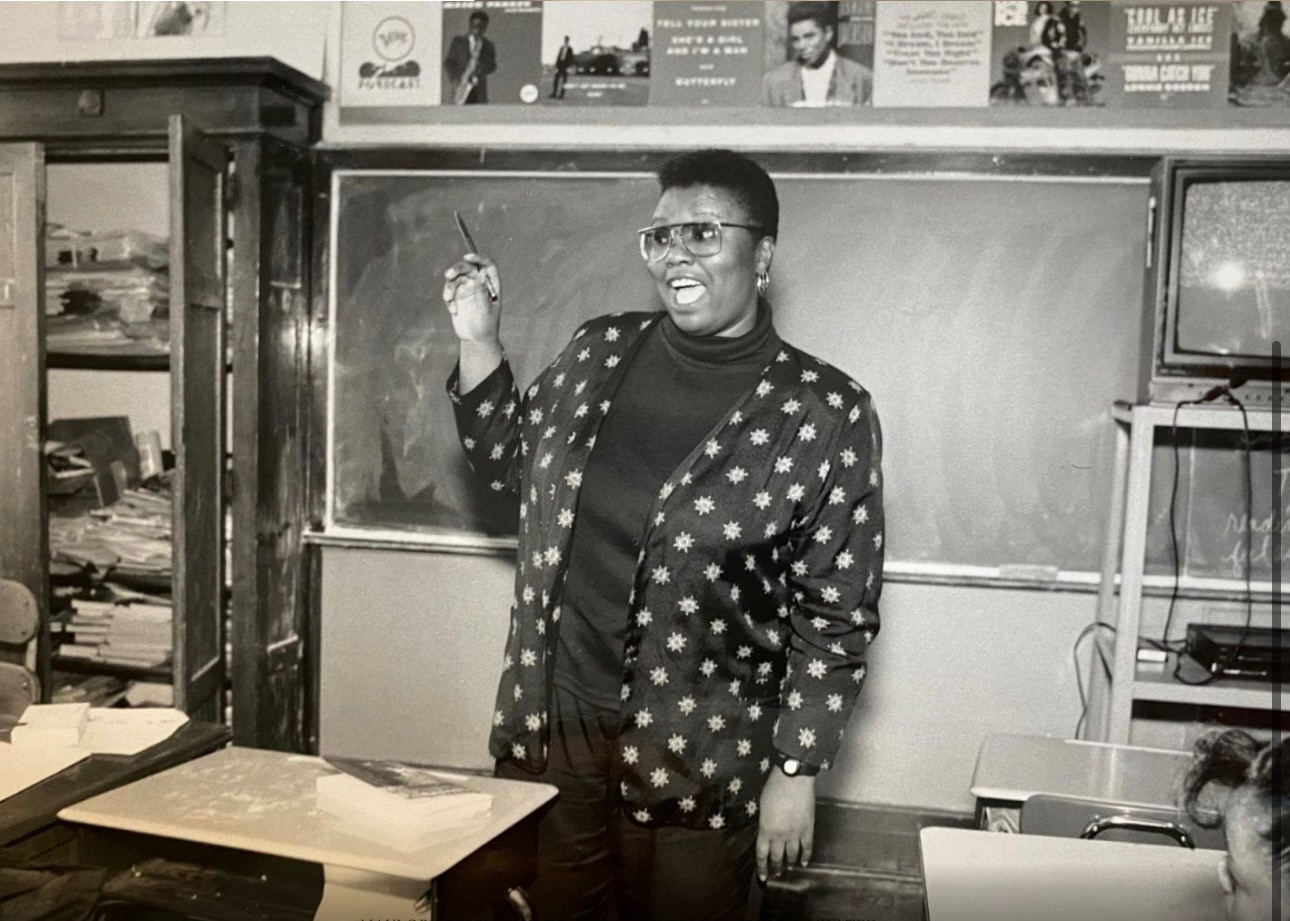

In parallel with her creative work, Naylor actively taught literature and creative writing at universities, including New York University, George Washington University, Boston University, Cornell University, and the University of Pennsylvania. She also served as a writer-in-residence at Newcomb College at Tulane University, where she shared her experience with young authors.

Among her other projects was editorial work on the anthology Children of the Night: The Best Short Stories by African American Writers from 1967 to the Present (1996), which became a modern continuation of the collection once compiled by Langston Hughes.

Gloria Naylor’s last novel, 1996, written in 2005, was an unexpected experiment—a fictional memoir in which Naylor combined personal experience with political themes. She wrote candidly about racism, isolation, and distrust of state institutions, claiming that the book’s protagonist becomes a victim of psychological pressure.

Influence and Awards

Gloria Naylor’s debut book not only won the National Book Award and the American Book Award in 1983 but also paved the way for further achievements. The writer received a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship (1985), the Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women (1986), a Guggenheim Fellowship (1988), and the Lillian Smith Book Award (1989) for her next novel, Mama Day.

Following her literary success, she immersed herself in the world of theater, film, and television. The writer later founded her own production company, One Way Productions, aiming to control the film adaptations of her works. She worked on screenplays, dreamed of bringing Mama Day to the big screen, and created dramatic projects about the fates of women deprived of freedom. Her stage adaptation of Bailey’s Cafe was produced in Connecticut in 1994.

After closing her company in 2000, Naylor gradually withdrew from public life. In 2009, she transferred her archives to Sacred Heart University, and they were later digitized at Lehigh University. Gloria left New York and moved to St. Croix in the Virgin Islands, where she lived out her final years. Gloria Naylor died on September 28, 2016, in Christiansted from heart failure. She was 66 years old.

Three years after her death, in 2019, an unfinished manuscript was published—Sapphira Wade, which Naylor had worked on for many years. This work became a kind of epilogue to her life: a story about strength, roots, and spiritual revival, which were always at the heart of her prose.

Gloria Naylor’s legacy is a literary world where African American women finally speak in their own voices. Her works remain a testament to courage, female solidarity, and an unbreakable spirit—the values that were the core of Naylor’s entire body of work.