Despite her outward coolness, a restrained sensibility lived within her—a love for beauty, memory, music, and friends. Her legacy continues to inspire the literary world, recreating the charm and complexity of American and European society from the late 19th to the early 20th century. Read on newyorka.info for more about one of the most famous female authors who delicately depicted the life, customs, and morality of the New York elite.

Little Pussy Jones

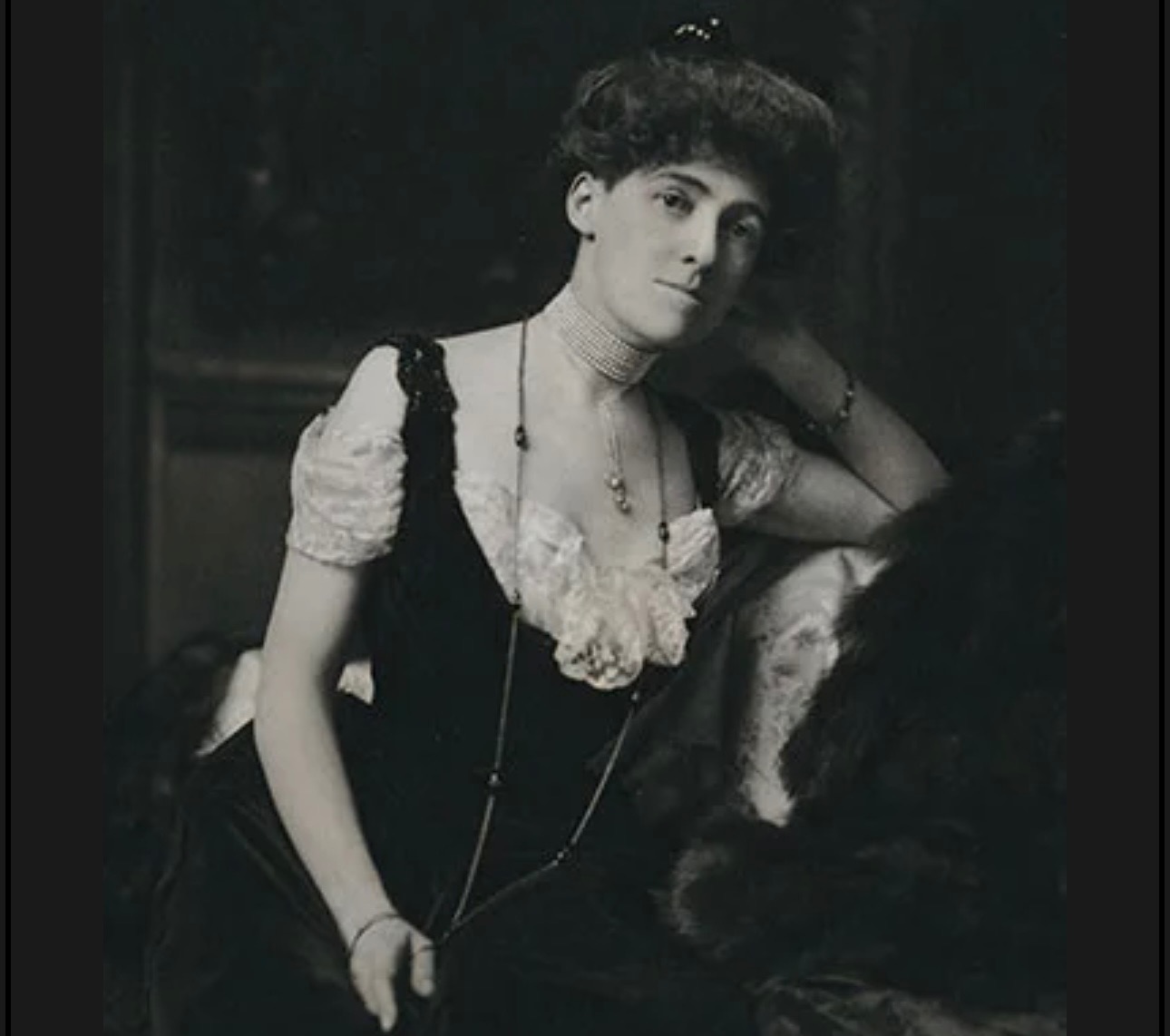

Edith Newbold Jones was born on January 24, 1862, in New York, during an era when America was still consumed by the fires of the Civil War. She came from a world where women were expected to be refined and silent, while men were rich and influential.

Her family belonged to the old New York aristocracy—the Joneses, Rhinelanders, and Stevens—the very families that built the city on money and morals. Her relatives included generals, landscape architects, and even Caroline Astor herself, the queen of New York high society.

Edith’s childhood was spent between the heavily curtained walls of her house on 23rd Street and endless travels through Europe. France, Italy, Germany, and Spain—all became her first school of observation. Little “Pussy,” as she was called at home, was taught by governesses; by age nine, she spoke three languages fluently.

The girl had a peculiar habit from an early age: she would walk around with an open book, inventing stories as she went. Her first writing attempts were serious; at 15, Edith translated the German poem “What the Stones Say” and received $50 for it—a significant sum for a young lady. But because writing was considered an unseemly occupation for a woman of respectable society, the work was published under a pseudonym.

Despite her mother’s ban on reading novels until marriage, Edith secretly borrowed books from her father’s library. She devoured the works of the classics, feeling that her real education was starting right there, in the quiet of the study.

In 1879, the young Jones debuted in New York society. She was allowed for the first time to bare her shoulders, put her hair up, and attend a dance hosted by Anna Morton, the city’s leading social matron. The girl experienced her first courtships, the first gossip, and the first disillusionments—all the experiences that would later turn into the pages of The House of Mirth and The Age of Innocence.

But Edith’s true debut was not at a ball, but at her writing desk. At fifteen, she secretly wrote her first novel, Fast and Loose—a story about the young and vain, which she did not dare to show anyone. Thus began the journey of the girl who would long be seen only as “Little Pussy Jones of the good family”—without anyone suspecting that she would become Edith Wharton, one of America’s most perceptive writers.

Between High Society, Literature, and War

In 1885, at the age of 23, Edith married Edward “Teddy” Robbins Wharton, a gentleman from a wealthy Boston family, 12 years her senior. Their marriage was united by shared interests in travel, aesthetics, and high society. From the marriage, three great passions emerged for Wharton: American houses, writing, and Italy. Trips abroad, especially to Italy, France, and England, were regular; every spring and summer, the couple would leave for several months, discovering the architecture, culture, and art of Europe. However, the late 1880s cast a shadow over their lives. Her husband suffered from chronic depression, causing their extensive travels to cease, and the family settled at the Mount estate in Lenox. Here, Edith wrote her first novels, studying the lives of the American elite.

The marriage lasted 28 years and ended in divorce in 1913, but this did not stop Wharton. She immersed herself in literature, creating over 85 short stories, novels, and books on interior and garden design.

During World War I, Edith found herself in Paris. Despite the danger, she remained in the city, actively helping refugees, the unemployed, and the wounded. Wharton opened workrooms for women, organized concerts, raised funds, and created the Children of Flanders Rescue Committee, which sheltered nearly 900 Belgian children. Her heroic efforts were recognized by the French government—Wharton was awarded the Chevalier of the Legion of Honor.

After the war, Edith settled in the French village of Saint-Brice-sous-Forêt, where she spent her summer and autumn months, and winters on the French Riviera. She later traveled to Morocco, again demonstrating her passion for the culture, architecture, and politics of other countries.

Between her estates, travels, and literary projects, Edith Wharton remained one of the most influential American writers, whose talent and life perspective combined sophistication with social depth.

The Writer Who Gave Shape to Morality

Edith Wharton is the writer who exposed the America of old manners and moral codes. Her work is a chronicle of a lost era in which honor, outward propriety, and social constraints stood above happiness.

- Novels.

Beginning with The Valley of Decision (1902), Wharton established herself as a chronicler of old New York—a society where even emotions were measured by decorum. Her first masterpiece followed: The House of Mirth (1905). This is the tragic story of Lily Bart—a woman destroyed by the ruthless rules of the world she sought to tame. Wharton portrays the upper class not as a brilliant stage but as a gilded cage. Subsequent novels—The Glimpses of the Moon (1922), A Son at the Front (1923), The Mother’s Recompense (1925), Twilight Sleep (1927), The Children (1928)—demonstrate Edith Wharton’s ability to combine moral analysis with an elegant style. Her last unfinished novel, The Buccaneers, is about American heiresses seeking freedom in Europe. It is an ironic but tender farewell gesture from the writer to her favorite motif—the woman broken by tradition.

- Novellas and Short Prose.

In shorter forms, Wharton revealed another side of her talent. Her short novel Ethan Frome (1911) became a classic of psychological realism. Other novellas—Madame de Treymes (1907), The Bunner Sisters (1916), In Vain (1918), Old New York (1924)—create a mosaic of stories where the past lives on in every shadow.

- Short Story Collections.

In collections such as The Greater Inclination (1899), The Descent of Man (1904), Tales of Men and Ghosts (1910), and Xingu and Other Stories (1916), Wharton proved herself a master of the short form. Her stories often have a Gothic flavor, but they are less about ghosts and more about allegories of guilt, memory, and unfreedom. In later collections, such as Certain People (1930), Human Nature (1933), and Ghosts (1937), Wharton argues that true fears reside not in the darkness but in the social masks we wear.

- Poetry.

Although Wharton is known primarily as a prose writer, her poetry collections—Verses (1878), Artemis to Actaeon (1909), and Twelve Poems (1926)—demonstrate her classical taste and penchant for harmony.

- Non-Fiction.

Few know that **Edith Wharton was the first woman in America to write a book on interior design: The Decoration of Houses (1897). Her travel essays—Italian Villas and Their Gardens (1904), Italian Backgrounds (1905), and In Morocco (1920)—reveal Wharton as a cultural anthropologist. Furthermore, during World War I, Edith became a journalist, writing reports such as Fighting France (1915) and French Ways (1919), where she demonstrated courage and empathy.

- Film and Theater Adaptations.

Edith Wharton’s works have been repeatedly brought to life on stage and screen. Among the most famous are The Age of Innocence, directed by Martin Scorsese (1993), and The House of Mirth (2000), starring Gillian Anderson.

Edith Wharton’s main strength lies in her ability to write about morality without moralizing.

She sees in every character not a sinner or a saint, but a person doomed to compromise between desire and duty. Edith Wharton’s work is a bridge between the old and the new world. She gave America a mirror in which its sophistication, hypocrisy, strength, and fatigue were reflected.

Triumph and Edith Wharton’s Final Chapter

In 1920, Edith Wharton created her masterpiece, The Age of Innocence, for which she won the Pulitzer Prize the following year, becoming the first woman in history to be awarded the prize. Although the literary judges initially favored Sinclair Lewis’s satire Main Street, the advisory board of Columbia Universityoverturned that decision, judging Wharton’s novel to be the best. Her talent was also recognized internationally; the writer was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1927, 1928, and 1930.

Wharton was close to many prominent intellectuals and artists of her time. Henry James, Sinclair Lewis, Jean Cocteau, André Gide, Theodore Roosevelt, Bernard Berenson, and Kenneth Clark were among her circle of friends.

In her sixties, Edith Wharton lived at her French country home, Le Pavillon Colombe, leading a planned and refined life: mornings were dedicated to writing, and afternoons to gardening and walks with her dogs. She was a passionate collector of antique wallpaper and a gardener, having created the famous Brocade Garden in Lenox. Wharton’s house was characterized by strict order; the servants adhered to a clear hierarchy, and dinners were served flawlessly.

In 1937, while working on an updated edition of The Decoration of Houses, Wharton suffered a heart attack and later, on August 11, died from a stroke. She was buried in Versailles with full military honors and recognition of her service as a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor.

Edith Wharton lived a life of detached dignity, remaining true to discipline, refinement, and intellectual aristocracy.