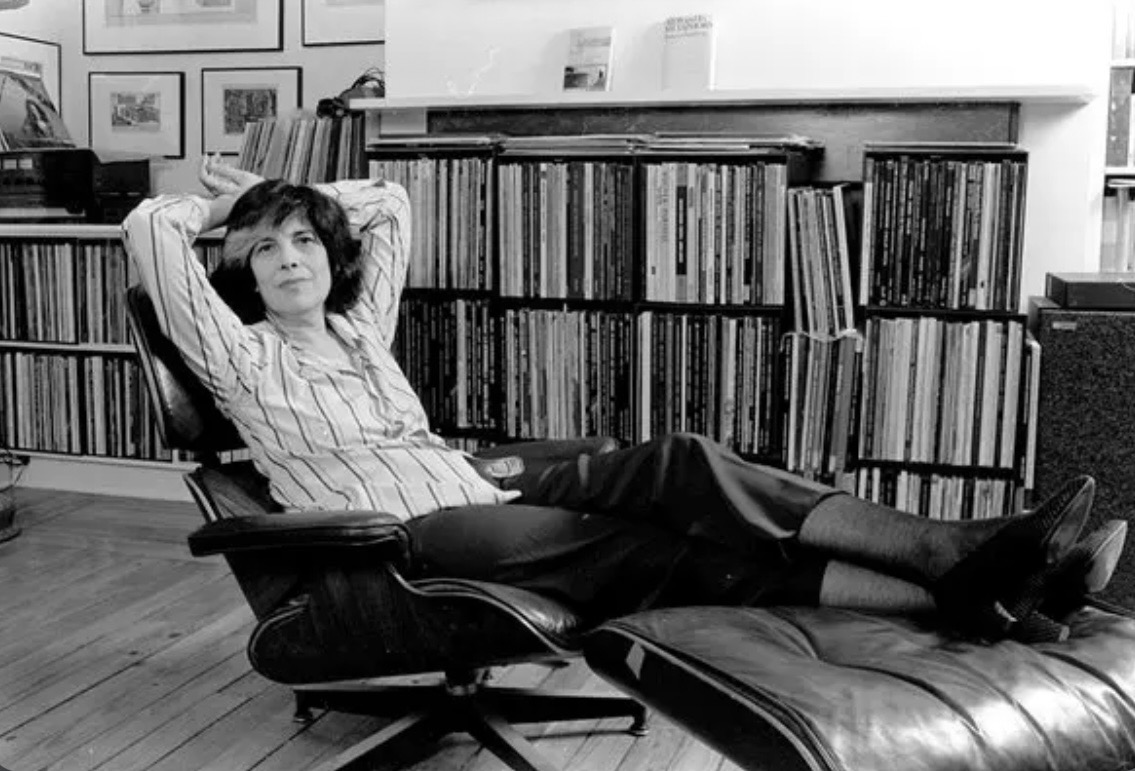

Her stance often provoked discussion—she boldly analyzed popular culture, elevated the value of aesthetics, and simultaneously actively advocated for human rights. In her works, Sontag covered a wide range of topics—from literature and philosophy to global politics, war, feminism, illness, and the phenomenon of photography. Read on newyorka.info for more about this New York cultural icon.

The Making of a Writer

Susan Sontag was born in New York in 1933 under the name Susan Lee Rosenblatt. Her parents, Mildredand Jack Rosenblatt, were Jews of Lithuanian-Polish descent. Her father managed a fur business in Tianjin, China, where he died of tuberculosis when his daughter was only five years old. After this, her mother returned to the U.S. and married officer Nathan Sontag. Susan’s childhood was lonely and cold. Her mother, prone to alcoholism, often left her daughters in the care of relatives. Sontag confessed that she felt abandoned and always cried at the movies when she saw scenes of parents and children reuniting. She sought solace in books—complex and adult. Reading became the girl’s escape and the foundation of her intellectual development.

At 15, Susan enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley. She later transferred to the University of Chicago, where she studied philosophy, history, and literature under intellectual figures such as Leo Straussand Kenneth Burke. At just 18, she graduated with honors and was inducted into the Phi Beta Kappa honor society.

In Chicago, Susan met sociologist Philip Rieff. Ten days after meeting, they married. Their marriage lasted eight years, producing their only son, David Rieff, who later became an editor and writer.

After their divorce, Susan received a fellowship from the American Association of University Women and continued her studies at Oxford, and then at the Sorbonne. In 1959, Sontag returned to New York and resumed custody of her son. She taught at Columbia University, Sarah Lawrence College, and City College of New York, all while developing her own voice in literature and cultural criticism. Her journey, from a lonely girl hiding in books to one of the most influential intellectuals of the 20th century, became the embodiment of intellectual power, a thirst for knowledge, and unwavering independence.

The Literary World of Susan Sontag

Susan Sontag entered literature as an experimenter who dared to break conventional forms and genre boundaries. Her debut novel, “The Benefactor,” in 1963, was an intellectual game with dream and reality—the story of a man seeking meaning through the philosophy of dreams. Four years later, “Death Kit” appeared—an even more bizarre and unsettling work that blended psychology, symbolism, and the absurd.

Recognition came to Sontag later. In 1986, her short story, “The Way We Live Now,” appeared in The New Yorker and became one of the first fictional texts to deeply and candidly describe the experience of the AIDS epidemic. Structured as a dialogue, it conveyed the fragmentation and unspeakable pain of the era—without melodrama, but with extraordinary empathy.

In 1992, Sontag achieved genuine popular success with the novel “The Volcano Lover,” a story about passion, art, and power inspired by the lives of Lord and Lady Hamilton. As the writer confessed, the idea came to her when she saw antique engravings of volcanoes in a London print shop near the British Museum. Her last novel, “In America” (2000), returned to historical themes—this time about the life of a Polish actress seeking a new calling in the United States. The book won Sontag the U.S. National Book Award.

Besides prose, Sontag wrote plays—including “Alice in Bed” and “Lady from the Sea”—and also directed four of her own films.

The Essayist Who Challenged Culture

Susan Sontag entered history as a thinker who forced a generation to see culture and art in a new light. Her essays are not just criticism or analysis but intellectual manifestos of the era, where philosophy collides with aesthetics, and art with morality.

The essay collection “Against Interpretation” (1966) became Susan Sontag’s programmatic work. It urged readers to reject moral pressure on art, stop searching for meaning in it, and start perceiving it physically, through sensation. The slogan “less interpretation—more sensation” made her the voice of the young generation of the 1960s, who sought liberation from authority and rigid ideologies.

In 1977, Sontag published the essay collection “On Photography,” for which she won the National Book Critics Circle Award. She explored how photographs changed human perception of reality. In her books “Illness as Metaphor” (1978) and “AIDS and Its Metaphors” (1988), Sontag debunked society’s habit of applying moral labels to diseases, from tuberculosis to cancer and AIDS. Her later work, “Regarding the Pain of Others” (2003), develops this theme—about how the depiction of war and suffering in the media transforms us from empathetic witnesses into indifferent consumers.

Although Sontag wrote novels, plays, and directed films, her essays made her a symbol of intellectual courage. Sontag’s texts are a dialogue between intellect and sensuality, an attempt to explain the world not through ideas, but through feeling.

“Art is not supposed to be explained,” she wrote, “it is supposed to change us.”

Criticism and Legacy

Susan Sontag always evoked extreme emotions—from admiration to irritation. Her intellectual sharpness and independence made her a symbol of the era and a target for criticism.

Sontag did not shy away from provocation. In 1982, she declared that communism was a variety of fascism, causing outrage even among left-wing intellectuals. After September 11, 2001, she again went against popular opinion, calling the tragedy a “terrible dose of reality.”

Some contemporaries considered her persona exaggerated. Tom Wolfe ridiculed her as a “tribune intellectual,” and Camille Paglia accused her of being a pretentious smarty-pants and detached from feminism:

“Nobody prevented Sontag from becoming a voice for women—her failures were entirely her own.”

Despite the controversies, after her death in 2004, Sontag’s influence was recognized as undeniable. Steve Wasserman called her “one of America’s most influential intellectuals,” and Eric Homberger—the “dark lady of cultural life” who changed the perception of art. It was thanks to her collection, “Against Interpretation,” that the analysis of pop culture became an academic discipline.

Sontag received numerous awards—from the National Book Critics Circle Award to the Jerusalem Prizeand the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. After her death, she was honored in Sarajevo, where the plaza near the National Theater was named after her, and in 2024, a crater on Mercury received her name.

Sontag’s archive, with over 17,000 documents, is housed at the University of California. As Margalit Fox wrote in The New York Times:

“She was called everything—brilliant, cold, arrogant, elegant, passionate, dogmatic—but no one ever called her boring.”

The Writer’s Personal Life

Susan Sontag openly acknowledged her bisexuality. She realized her attraction to women as a teenager and wrote in her diary:

“I feel I have lesbian tendencies (how reluctantly I write this).”

She had her first romantic experience with a woman at 16. During her college years, Sontag lived with writer and model Harriet Sohmers Zwerling. She later had relationships with Cuban-born playwright María Irene Fornés, and after their breakup, with Italian aristocrat Carlotta Del Pezzo and German scholar Eva Kollisch. She is also credited with romances with artists Jasper Johns and Paul Thek. One of her most notable connections was her affair with the poet Joseph Brodsky, which influenced her worldview and deepened her understanding of anti-Soviet writers.

Sontag’s last relationship was with photographer Annie Leibovitz, which lasted from the late 1980s until Susan’s death. The women never lived together but maintained apartments near each other.

Susan Sontag passed away on December 28, 2004, in New York City at the age of 71. The cause of death was complications from myelodysplastic syndrome, which developed into acute leukemia. The final period of her life and her struggle with illness were documented by her son, writer David Rieff.

Susan Sontag remained a figure who combined intellectual power, emotional depth, and personal independence. Her life is a story of searching for truth, love, and the courage to be oneself. She forever remained a symbol of female intellectual freedom and moral honesty that would not yield to any taboos.