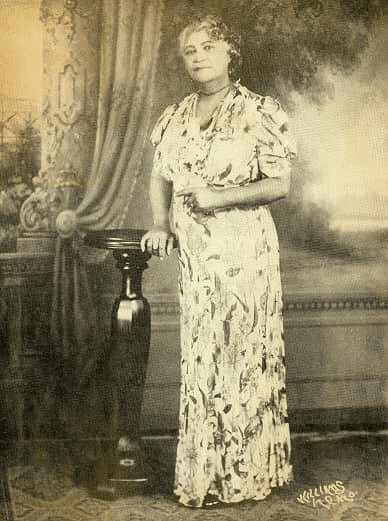

For centuries, women around the world have played a crucial role in the development of society and in fields like politics, culture, activism, and philanthropy. This is despite the fact that women’s rights were long restricted. Among these influential figures of the 19th and 20th centuries was a New York native, Fredericka Douglass Sprague Perry. We’ll explore her life story further on newyorka.

What Do We Know About Fredericka’s Early Years?

Fredericka was born in Rochester, New York, back in 1872. She was the daughter of a prominent American teacher and activist who founded the National Association of Colored Women. She was also the granddaughter of Frederick Douglass—the American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman after whom she was named. Given her lineage, it’s no surprise that Fredericka had a strong social conscience from a young age. Growing up in a world rife with inequality and injustice, her beliefs were clearly defined early on. From her grandfather, she inherited resilience and determination—all the necessary qualities of a leader.

She attended public school in Washington and later moved to New York, where she enrolled in the Mechanics Institute.

Throughout her life, both in school and at the institute, Fredericka faced issues of inequality that also plagued her community. She witnessed firsthand how marginalized communities struggled and how their voices and rights were ignored due to prejudice. This awareness fueled her passion for advocacy. Fighting for equality became her life’s work.

Activism in Fredericka’s Life

Fredericka’s active involvement in civil rights began with her participation in the African American Women’s Club movement. This was a social movement that spread not only in New York but also in other U.S. cities. The main idea behind this movement was to promote the belief that women had a moral duty and responsibility to change public policy.

For a time, Fredericka worked in a juvenile court, where she focused on cases involving minors. She paid special attention to cases of abuse and neglect of Black foster children. All too often, they were sent to state institutions with other juvenile offenders, where they were subjected to further cruelty and had to remain until they came of age.

After a while, she spearheaded the creation of the Missouri State Association of Colored Girls. Soon after, their work led to the founding of the Colored Big Sister Home for Girls.

Fredericka also served as the president of the National Association of Colored Girls. She dedicated herself wholeheartedly to this cause, working tirelessly to dismantle barriers that hindered progress in civil rights. Under her leadership, she not only created organizations for the Black community but also organized protests, grassroots initiatives, and more. She lobbied legislators and was unwavering in her quest to achieve change and a better life for her community.

Fredericka’s activism was broad. She also helped found the Civic Protective Association in Kansas City and served as a trustee for the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association. She was also a member of the John Brown Memorial Association.

Philanthropy, Personal Life, and Death

Fredericka deeply understood that true transformation required more than protests. For her, philanthropy was a way to address the systemic issues plaguing her community. Throughout her life, Fredericka invested her resources in initiatives aimed at supporting the underprivileged and marginalized. She funded educational programs for low-income youth and created shelters for the homeless. Her charitable work touched countless lives and offered hope for a better future.

From a young age until the very end, Fredericka always lent a hand to those in need and relentlessly fought for their rights, equality, and opportunities.

She once traveled to Missouri, where she taught home economics at Lincoln University. It was there that she met her husband, Dr. John Edward Perry. He, like Fredericka, fought for Black rights and worked to improve their lives. He founded the first private hospital for Black people in Kansas City, the Wheatley-Provident Hospital. To support her husband’s endeavors, Fredericka worked alongside him at the hospital for a time.

In 1943, at the age of 71, the heart of the distinguished activist and philanthropist stopped beating. She passed away in the Wheatley-Provident Hospital in Kansas City, the very hospital her husband had founded.